Archive for the ‘creative writing’ Tag

“Apology for Absence”

At a reading I attended at the end of last year, a poet friend (very supportive of my work) asked if I’d retired.

I understood her to be referring to my not having worked the past three years. I was in chemotherapy the last half of 2016, and I’ve been recovering ever since. My vitality and acuity are presently too volatile for me to commit to teaching fifteen weeks at a go. I tried in the fall of 2018, but had to surrender the single class I was teaching mid-November…

I was more than a little disturbed when through my mental fog it appeared to me she hadn’t been asking about my job status but my writing and publication record. (That it took me so long to pick up on her meaning is an index of my state). My last trade publication was March End Prill (Book*Hug, 2011), a long poem that, itself, had been composed almost a decade before it appeared in print.

Lately, I’ve taken to joking I have the creative metabolism of a pop star: about twelve poems a year, which, were I pop singer, would be enough for a new album. Given that many poetry presses prefer manuscripts of over eighty pages or so, that pace of production would ideally result in a new book every seven years or so. Were it only so simple.

Even for someone with three trade editions under his belt, every new manuscript is a new challenge to get published. Indeed, the last two collections I’ve collated have failed to find a publisher. On the one hand, I’m no networker. On another, the work has always been against the grain. Tellingly, the last editor to turn down my latest manuscript did so on the basis of an understanding of its poetics the opposite of my own.

Moreover, I eschew a practice increasingly common, to compose “a book”. Often a poet will pick up and follow the thread of a theme or as often crank a generative device. Sometimes such efforts are successful, and I can appreciate the urge and sentiment that goes into this approach, when it’s not the result of the pressures of reigning expectations. However, as my earliest mentor once quipped concerning the composition of a collection: “A book is a box.”

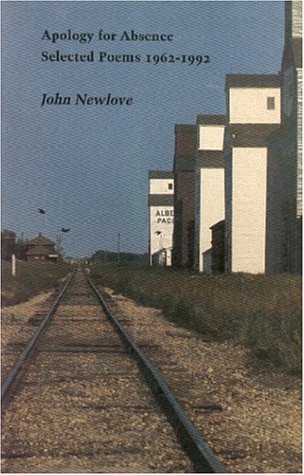

Which brings me to the title of this post. Apology for Absence is the title of John Newlove’s  selected poems (Porcupine’s Quill, 1993), a famously laconic poet, known, among other things, for his diminishing productivity over the years. But Newlove holds a more profound importance for me, personally. As I write in a poem from Ladonian Magnitudes:

selected poems (Porcupine’s Quill, 1993), a famously laconic poet, known, among other things, for his diminishing productivity over the years. But Newlove holds a more profound importance for me, personally. As I write in a poem from Ladonian Magnitudes:

Because John Newlove the Regina Public Library’s writer-in-residence gave me his Fatman and reading it in the shade on the white picnic table on the patio in our backyard thought “I can do that!” and wrote my first three poems

I like to think that happened when I was fourteen, but a little research proves I must have been a year or two older. At any rate, however much I admire and envy the productivity of a D. H. Lawrence or Thomas Bernhard, I seem to have followed Newlove’s example in this regard. (It’s a long story). Poetically, there are worse models.

No, I haven’t retired. Nor am I absent, MIA. I’m hard at work, at my own work, going my own direction at my own pace, trusting some will be intrigued if not charmed enough to tarry along.

Why “you can’t teach writing”

“We never hear that music cannot be taught, painting cannot be taught, filmmaking cannot be taught. Writing is fraught with more industrial insecurities, I fear, than some of the other disciplines.”

Paul Vermeersch writes these two sentences in a passing response to “The Persistence of the Resistance to Theory”. The distinction that troubles him between “writing [and] some of the other disciplines” may be accounted for by some arts being more mediate than writing. Music, painting, filmmaking, photography, and sculpture, for that matter, all demand acquaintance with an instrument: obviously in the case of music; brush, pigments, palette and other implements in the case of painting; and so on. Writing, however, appears to the layperson to require only literacy or in the case of oral language arts even only the voice. It might be objected singing and dancing are as immediate as the voice and body, but both seem special occasions of each, speaking and writing more basic, as thinking, the dialogue of the soul with itself or what one attempts to merely attend in meditation, appears to intimate. Of course the writer and writing teacher beg to differ: the poem or story are not just thinking or talking; creative writing is an art or craft where language is the medium worked. No matter how spontaneous or plain spoken a poem, say, may appear—and even if it is in fact spontaneous or improvised—its language is organized in an artificial manner.

The very words “creative writing workshop” imply—and its practice is premised upon the assumption—that creative writing is a teachable, learnable craft. If the master is to teach the apprentice, they must share a metalanguage, a discourse that articulates the materials and practices of that art and that expresses value judgments. This discourse may be called a “poetics”, not of the theoretical kind typified by Aristotle’s Poetics—a description, analysis, and evaluation of the art by a non-practitioner—but more akin to Horace’s Ars Poetica, practical guidance of an acknowledged master offered to an aspiring neophyte. Ironically, while creative writing teachers will vehemently defend the artificiality of literary language, too often (in my experience, at least) they assume the language of their poetics is somehow natural and its value system intuitive. Worse, too often, precisely because the terms of their poetics is assumed to be natural, they assume it is as unproblematically shared with the apprentice.

Despite the distinction between theoretical and practical poetics, the practical language of the workshop is heavily indebted to the theoretical language of the English class, i.e., literary criticism. Of course, the corollary is also true: the language of the master informs that of the teacher: the poetics of Horace, Wordsworth, Coleridge, or Henry James are fed back in to the merely scholarly study of literature. But creators learn their terms in the classroom. Neither scholarly nor creative discourse can claim priority; they are mixed at the source, because the art of writing assumes what the ancients called grammar, literacy, and one’s taught reading and writing in school. Not only are the languages of criticism and creation impossible to disentwine, they are also diverse and relative. The notion of poetry as craft was energetically applied by the Russian Futurists before the Great War, for example, with their doctrine of “the self-sufficient word” and their emulation of the factory worker or craftsman, an approach summed up neatly by the painter Dmitriev: “the artist is now simply a constructor and technician.” Their poetic, as articulated by their scholarly co-workers the Russian Formalist critics, spoke of “materials” and “devices” with a dispassionate, scientific technicality and precision that makes the terminology of most criticism or poetics seem quaint. This approach to the craft of poetry finds analogues in anglophone poetics, in the “bald statement” William Carlos Williams makes in his introduction to The Wedge (1944), “A poem is a small (or large) machine made of words,” and in creative writing pedagogy where the Russian Formalist concepts of “defamiliarization” and “device” are used alongside exercises in proceduralist composition in the manner of the OULIPO or present-day Conceptualism. That such poetics also find inspiration and conceptual resources in literary theory should not go unremarked.

Regardless of the impossibility of a purely practical poetics, the knotiness of poetics, criticism, and theory being snarled together, or debates about the merits of competing creative writing pedagogies, doubts remain whether writing can be taught. Such skepticism cannot be dismissed as easily as pointing out it depends upon an outmoded, questionable notion of genius. Who can deny that the increasing plethora of creative writing programs results in an increasing homogenization of literary practice? My own experience is telling: every year I teach the latest Journey Prize Stories and invariably I find the creative-writing-school-trained jury members award first prize to the story worthy an A+ in a creative writing class while the edgy, lively work, worthy an A for Art, is overlooked, precisely because of the prejudices inculcated in the course of the jurors’ educations. What can be taught is technique, but technique without the natural gift of talent is merely mechanical or at best competent. The art of writing (or music, or painting, etc.) can be taught, but not what might make it Art.

Comments (12)

Comments (12)